If the world adopted a plant-based diet we would reduce global agricultural land use from 4 to 1 billion hectares

Published 11 March 2021

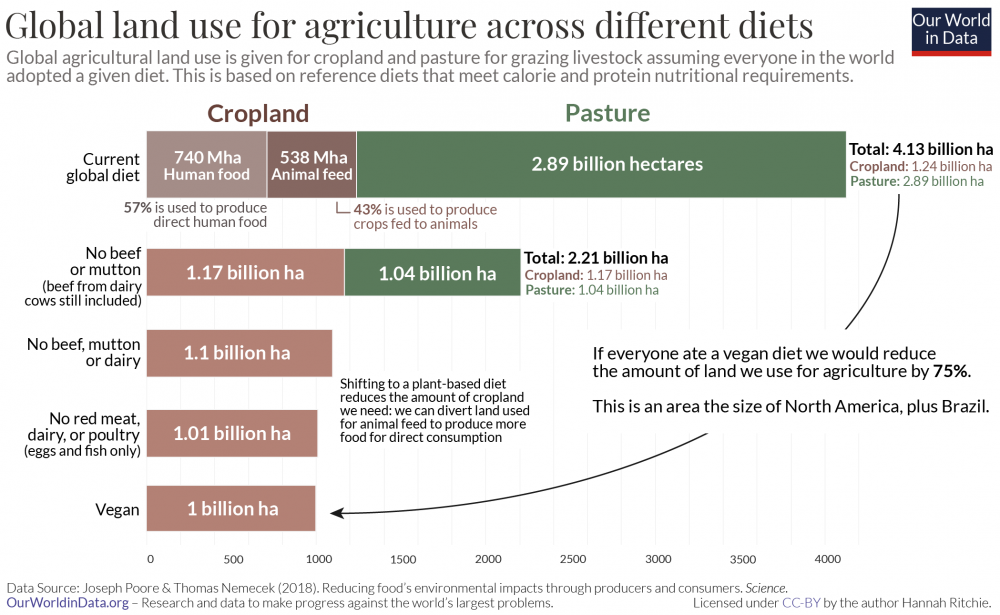

Research suggests that if everyone shifted to a plant-based diet we would reduce global land use for agriculture by 75%.

Our World in Data presents the data and research to make progress against the world’s largest problems.

This blog post draws on data and research discussed in the entry on Environmental impacts of food production.

Summary

Half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture, with most of this used to raise livestock for dairy and meat. Livestock are fed from two sources – lands on which the animals graze and land on which feeding crops, such as soy and cereals, are grown. How much would our agricultural land use decline if the world adopted a plant-based diet?

Research suggests that if everyone shifted to a plant-based diet we would reduce global land use for agriculture by 75%. This large reduction of agricultural land use would be possible thanks to a reduction in land used for grazing and a smaller need for land to grow crops.

—

The expansion of land for agriculture is the leading driver of deforestation and biodiversity loss.

Half of the world’s ice- and desert-free land is used for agriculture. Most of this is for raising livestock – the land requirements of meat and dairy production are equivalent to an area the size of the Americas, spanning all the way from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego.

The land use of livestock is so large because it takes around 100 times as much land to produce a kilocalorie of beef or lamb versus plant-based alternatives. This is shown in the chart.1 The same is also true for protein – it takes almost 100 times as much land to produce a gram of protein from beef or lamb, versus peas or tofu.

Of course the type of land used to raise cows or sheep is not the same as cropland for cereals, potatoes or beans. Livestock can be raised on pasture grasslands, or on steep hills where it is not possible to grow crops. Two-thirds of pastures are unsuitable for growing crops.2

This raises the question of whether we could, or should, stop using it for agriculture at all. We could let natural vegetation and ecosystems return to these lands, with large benefits for biodiversity and carbon sequestration.3 In an upcoming article we will look at the carbon opportunity costs of using land for agriculture.

One concern is whether we would be able to grow enough food for everyone on the cropland that is left. The research suggests that it’s possible to feed everyone in the world a nutritious diet on existing croplands, but only if we saw a widespread shift towards plant-based diets.

Related charts:

Land use of foods per 100 grams of protein

Land use of foods per kilogram

More plant-based diets tend to need less cropland

If we would shift towards a more plant-based diet we don’t only need less agricultural land overall, we also need less cropland. This might go against our intuition: if we substitute beans, peas, tofu and cereals for meat and dairy, surely we would need more cropland to grow them?

Let’s look at why this is not the case. In the chart here we see the amount of agricultural land the world would need to provide food for everyone. This comes from the work of Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek, the largest meta-analysis of global food systems to date.4 The top bar shows the current land use based on the global average diet in 2010.

As we see, almost three-quarters of this land is used as pasture, the remaining quarter is cropland.5 If we combine pastures and cropland for animal feed, around 80% of all agricultural land is used for meat and dairy production.

This has a large impact on how land requirements change as we shift towards a more plant-based diet. If the world population ate less meat and dairy we would be eating more crops. The consequence – as the following bar chart shows – would be that the ‘human food’ component of cropland would increase while the land area used for animal feed would shrink.6

In the hypothetical scenario in which the entire world adopted a vegan diet the researchers estimate that our total agricultural land use would shrink from 4.1 billion hectares to 1 billion hectares. A reduction of 75%. That’s equal to an area the size of North America and Brazil combined.

Cutting out beef, mutton and dairy makes the biggest difference to agricultural land use as it would free up the land that is used for pastures. But it’s not just pasture; it also reduces the amount of cropland we need.

Original Article > by Hannah Ritchie, Our World In Data

Endnotes

-

This data is based on the global median land use of different food products as presented in Poore and Nemecek (2018). This meta-analysis looked at the environmental impacts of foods covering 38,7000 farms in 119 countries. For some foods there is significant variability from the median land use depending on how it is produced. We look at these differences here.

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987-992.

-

An estimated 65% of land used for grass for grazing cattle is not suitable for growing crops.

Mottet, A., de Haan, C., Falcucci, A., Tempio, G., Opio, C., & Gerber, P. (2017). Livestock: on our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate. Global Food Security, 14, 1-8.

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987-992.

-

Hayek, M. N., Harwatt, H., Ripple, W. J., & Mueller, N. D. (2020). The carbon opportunity cost of animal-sourced food production on land. Nature Sustainability, 1-4.

-

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987-992.

-

Note that this breakdown of agricultural land use differs slightly from the breakdown of global land use from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for a few reasons. First, this view only includes cropland and pasture used to produce food. Allocation of crops towards industrial uses e.g. biofuels is not included. In UN FAO breakdowns, it is included. Secondly, the amount of land that qualifies as ‘pasture’ depends on definitions surrounding livestock density and other aspects of land management. The extent of ‘rangelands’ – land used to raise livestock but at a relatively low density – can vary from study-to-study. So, while the UN FAO data suggests 50% of habitable land is used for agriculture, Poore and Nemecek (2018) put this figure at 43%.

-

This data is sourced from the meta-analysis study by Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek (2018), published in Science. Many other studies have looked at this question and found exactly the same result: that if everyone shifted to a vegan diet, we would need less agricultural land (and cropland) specifically.

Hayek, M. N., Harwatt, H., Ripple, W. J., & Mueller, N. D. (2020). The carbon opportunity cost of animal-sourced food production on land. Nature Sustainability, 1-4.

Searchinger, T. D., Wirsenius, S., Beringer, T., & Dumas, P. (2018). Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature, 564(7735), 249-253.

Recent News

-

Dogs Thrive on Vegan Diets, Demonstrates the Most Comprehensive Study So Far

The longest, most comprehensive peer-reviewed study so far has demonstrated that dogs fed nutritionally-sound vegan diets maintain health outcomes as well as dogs fed meat.

-

Vegan YouTube Channels – Our Top Picks

Vegan Easy’s YouTube channel recommendations to help you on your vegan journey.

-

Pamela Anderson’s New Vegan Cookbook: A Culinary Journey of Love and Compassion

Pamela Anderson, the iconic Hollywood actress and passionate animal rights advocate, is set to captivate the culinary world with her upcoming vegan cookbook titled "I Love You: Recipes from the Heart."

-

January 2024 Vegan Easy Challenge Recap

People from around the world began their 2024 with a peaceful start by taking the 30-day Vegan Easy Challenge.

-

Discover the Culinary Delights of Byron Bay’s Newest Plant-Based Cooking School

Learn the sublime art of plant-based cuisine at Katie White's new cooking school in Byron Bay

-

Beyond Romance: Encouraging Vegan Themes and Animal Protection in the Growing World of K-Dramas

The global popularity of K-dramas and growing interest in veganism present a unique opportunity to foster positive change

Leave a Comment